Harbour porpoise strandings

A regional perspective

Harbour porpoises are the most abundant cetaceans in the North Sea. In the years to come, more offshore wind parks will be developed in the southern North Sea. To preserve a sustainable environment for the harbour porpoise and minimise the effects on these animals, Wozep is looking at several aspects of harbour porpoise ecology and the impact on the population as seen in disturbance models.

However, that process is far from straightforward. It is important to know whether we are dealing with a single homogenous population in the North Sea, whether there are maybe age- or sex-specific differences in specific locations, and whether there are subpopulations. The standard monitoring approach for studying abundance and distribution is the aerial survey, which cannot be used to investigate population-specific parameters such as sex and age or potential changes in populations or sub-populations. However, the countries on the southern North Sea all record and investigate strandings of harbour porpoises. It was therefore decided to look at the information collected during these stranding studies to see if it was possible to establish a clearer picture of porpoise distribution in the North Sea and changes in that distribution in space and time.

Photo 1: A stranded porpoise on the Dutch coast (source: Utrecht University).

The challenge here is that stranding records to date have not extended beyond national borders. So they lack the ecologically relevant scale. Given this, Rijkswaterstaat commissioned a study of spatiotemporal stranding patterns throughout the North Sea region. This study was led by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Utrecht University, with data contributions from the stranding networks of the United Kingdom, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, and, of course, the Netherlands. The data included at least dates and locations, as well as sex and age class (based on total length) when available.

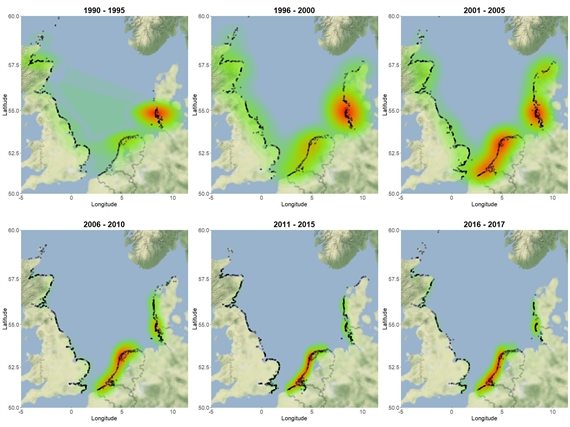

Over sixteen thousand individual harbour porpoise strandings were recorded in the southern North Sea between 1990-2017. This is the first time that data from the individual stranding networks have been combined for an ecosystem-wide assessment. The main conclusions of the analysis were that the number of strandings has increased significantly since 2004 in the southern North Sea, while remaining stable in the other regions. This also shows that the highest numbers of dead porpoises – mainly juvenile males – were found on the Dutch coast. The data also showed potential areas of particular importance for calving: the majority of neonates were found on the coasts of Denmark and Germany, but also on the coasts of the Dutch Wadden islands in the late calving season.

Image 1: Intensity of strandings along the North Sea coast at five-year intervals. Intensity from low to high indicated by green to red. (source: Utrecht University).

It was not possible to draw conclusions from the data about the underlying causes of the increase in strandings. It is therefore still unclear whether the general increase was simply due to an increase in local abundance, to elevated mortality levels or even to increased monitoring on the coasts. A follow-up study has therefore been initiated, primarily to determine whether stranding frequencies on the Dutch coast can be explained by the local population density.

Population density on the Dutch coast is determined on the basis of standardised sightings by numerous volunteers, who have been active for many years. Comparing the stranding data with these observations shows that sightings and strandings have indeed both increased since the first decade of the millennium and that there are considerable inter-annual fluctuations. However, in some years, excessively high stranding numbers were seen in particular periods while sightings had not increased, suggesting unusual mortality events. These events may be a result of factors such as a rise in human activity offshore, or of natural causes such as disease or a population approaching carrying capacity. Environmental factors such as prevailing wind direction could also play a role. However, the findings warrant further in-depth investigation into the health status and the causes of death in individuals stranded before, during and after such events. A more in-depth investigation of the relationship between stranding patterns and environmental variables is also needed.

Photo 2: Collection of data on stranded animals by the volunteers of the Dutch stranding network (source: Utrecht University).

The analyses were funded by Rijkswaterstaat – Wind op Zee Ecologisch Programma – (Wozep: project numbers 31141256 and 31153649). Stranding records were provided by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, the Fisheries and Maritime Museum of Esbjerg and the Natural History Museum of Denmark, the Institute for Terrestrial and Aquatic Wildlife Research, Hannover, Germany, Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden and the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) for the first study. Coastal sighting records and stranding records were obtained through the Dutch sea-watchers and Naturalis Biodiversity Leiden in the second study and this study was carried out in collaboration with Wageningen Marine Research and the Dutch Royal Institute of Sea Research. Two papers are currently being drafted for publication in scientific journals, after which the full details of both studies will be posted on the Wozep portal.